The Political Philosophy of E. M. S. Namboodiripad and Its Relevance to Tripura’s Left Politics

Abhishek Bhowmik

February 13, 2026

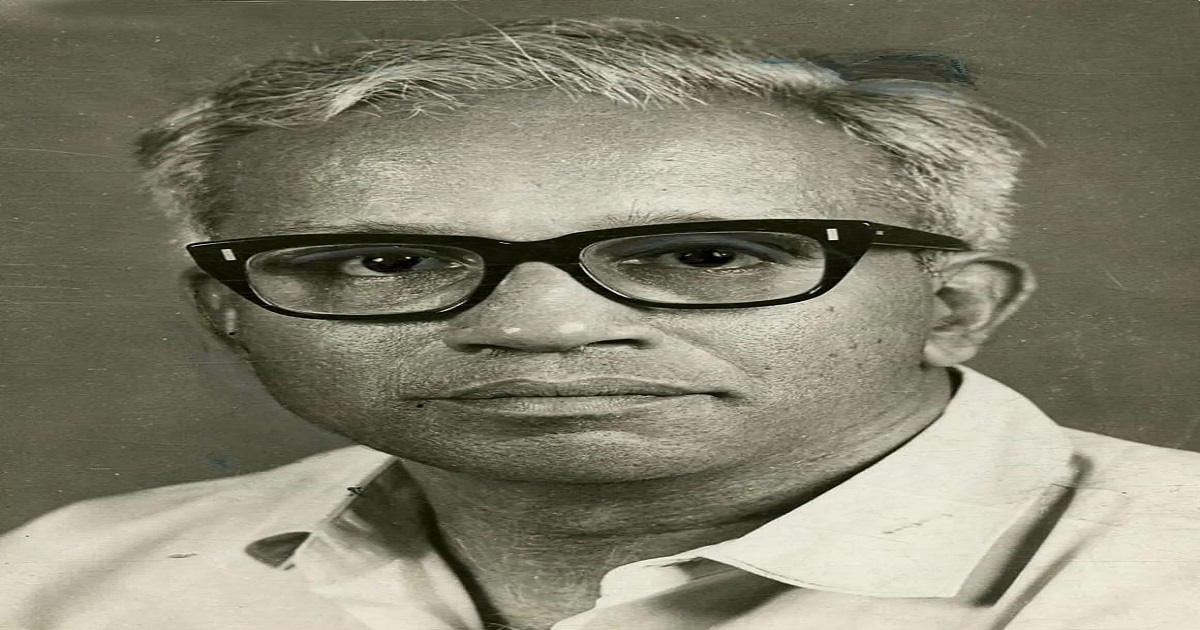

E. M. S. Namboodiripad (1909-1998) was one of the foremost Marxist theoreticians and mass leaders in India. As the first elected Communist Chief Minister in the world through a parliamentary process in India (Kerala, 1957), EMS combined Marxist theory with Indian social realities. His political philosophy was rooted in three core pillars: (1) dialectical materialism adapted to Indian conditions, (2) class struggle linked with caste and social reform, and (3) the use of parliamentary democracy as a terrain of mass struggle. These principles remain deeply relevant to the Left movement in Tripura.

First, EMS emphasized the “Indianization of Marxism.” He argued that Marxism could not be mechanically copied from Europe but must be historically contextualized. In Kerala, he analyzed the semi-feudal agrarian structure, caste oppression, and colonial legacy. Similarly, Tripura’s

socio-economic structure is unique: according to Census 2011, Scheduled Tribes constitute about 31.8% of the population, while Scheduled Castes are around 17%. The Left in Tripura, especially under leaders like Nripen Chakraborty and Manik Sarkar, adopted a localized strategy that combined tribal rights, land reforms, and Bengali refugee rehabilitation. This reflects EMS’s methodological insistence that Marxism must respond to concrete material conditions.

Second, EMS integrated class struggle with social reform movements. Unlike a narrow economistic interpretation of Marxism, he recognized caste as a material social force. In Kerala, the Communist movement drew strength from anti-caste struggles and peasant mobilizations. Tripura’s Left politics similarly engaged with ethnic identity and autonomy demands. The establishment of the Tripura Tribal Areas Autonomous District Council (TTAADC) in 1982 (brought under the Sixth Schedule in 1985) was a strategic attempt to address tribal aspirations within a constitutional framework. This approach resonates with EMS’s thesis that democratic decentralization and cultural autonomy can strengthen class unity rather than weaken it.

Third, EMS viewed parliamentary democracy not as an end but as a means for advancing people’s struggles. He rejected both reformist parliamentarism and ultra-left adventurism. His 1957 government in Kerala introduced radical land reforms and education bills within constitutional limits. In Tripura, from 1978 to 2018 (35 years with brief interruptions), the Left Front implemented land redistribution, expanded literacy, and strengthened rural local bodies. By the early 2010s, Tripura’s literacy rate rose above 87%, surpassing the national average (74% in 2011). This demonstrates how parliamentary participation, when combined with grassroots mobilization, can produce measurable socio-economic gains—an approach fundamentally aligned with EMS’s strategy.

Another important dimension of EMS’s philosophy was federalism and center-state relations. He consistently argued for stronger state autonomy within a cooperative federal framework. Tripura, being a small border state sharing 856 km of international boundary with Bangladesh, faces unique security and economic challenges. The Left’s emphasis on federal rights, financial devolution, and protection of state interests echoes EMS’s long-standing critique of excessive centralization in Indian politics. For Tripura, which depends significantly on central grants, the question of fiscal federalism remains crucial.

Ideologically, EMS believed in building broad democratic alliances. He supported the concept of a “Left and Democratic Front” to counter communal and reactionary forces. Tripura’s political history reflects this line. The Left Front united workers, peasants, tribal communities, minorities, and middle

classes under a common platform. During Manik Sarkar’s tenure (1998-2018), Tripura was often cited for relatively low levels of communal violence compared to many other states. This stability was not accidental but a product of consistent mass-based politics and secular mobilization—again reflecting EMS’s emphasis on secular-democratic unity.

At the organizational level, EMS stressed ideological education and inner-party democracy. He wrote extensively on Marxist theory, Indian history, and party-building. Tripura’s Left movement historically invested in cadre education through party classes and mass organizations such as student and youth fronts. For a politically conscious state like Tripura, where voter turnout often exceeds 85%, ideological clarity and mass contact remain decisive factors. EMS’s insistence on political education as the backbone of party strength holds continued relevance, particularly in an era of media-driven politics and rapid ideological polarization.

However, the contemporary scenario also demands critical reflection. Since 2018, the Left in Tripura has faced electoral setbacks. EMS himself argued that Marxist parties must continuously reassess their tactics in changing socio-economic conditions. The rise of identity politics, digital campaigning, and welfare-centric populism requires strategic innovation without ideological dilution.

EMS’s method—concrete analysis of concrete conditions—suggests that Tripura’s Left must

re-evaluate class composition, employment patterns, youth aspirations, and the impact of migration and border trade.

Numerically, Tripura’s economy remains predominantly service-oriented, with limited industrialization. Unemployment among educated youth has been a persistent issue. EMS’s framework would interpret this not merely as an economic statistic but as a structural contradiction of peripheral capitalism. Therefore, policy focus on public investment, rural employment, cooperative sectors, and decentralized planning could revive Left credibility. His emphasis on land reforms and public education also remains instructive in addressing inequality and social mobility.

In conclusion, the political philosophy of E. M. S. Namboodiripad offers both a theoretical compass and a practical roadmap for Tripura’s Left politics. His synthesis of Marxism with Indian realities, his commitment to democratic processes, his integration of class with caste and regional questions, and his stress on federalism and secular unity remain profoundly relevant. For Tripura—a state shaped by demographic complexity, border geopolitics, and a rich history of Left governance—the EMS legacy is not merely historical memory but a living guide. The future of the Left in Tripura will depend on how creatively and rigorously it can apply EMS’s dialectical method to contemporary challenges while remaining rooted in mass struggles and constitutional democracy.

(Tripurainfo)

more articles...